I don’t know why I’ve always felt this way, but I have consistently loved Scotties even as a young girl. Why is that? Well, I’m not really sure. I don’t recall ever seeing one as a kid other than the little silver Monopoly dog that we all know so well. I certainly never owned one myself. We had an assortment of family mutts and various purebred dogs throughout my childhood. None of them were Scotties, and yet Scotties have always been on my mind. I suppose it’s no surprise that I now own three of them and breed the occasional litter as well.

Back then Scotties had the reputation of being a sturdy breed. They were considered to be a relatively healthy and a wise choice for the savvy buyer. I had always held this in my mind as hard, indisputable fact. Imagine my surprise, then, to discover that this may not be an accurate representation any longer.

A few years after I met Tori, I started researching the breed in earnest. What I discovered was heartbreaking. Between 1975 and 1995, the incidence of bladder cancer in dogs increased by over 600%. Leading the charge among the affected breeds were Scottish Terriers, who have a twenty-fold increased risk to develop a specific form of bladder cancer called Transitional Cell Carcinoma. Other than TCC, Scotties suffer from high rates of craniomandibular osteopathy, Von Wilebrand’s Disease, Cushing’s Disease, liver ailments and, of course, the famous Scottie Cramp.

If you know the history of Scottish Terriers, this sudden downturn of health is not altogether surprising. Scotties were, at one time, one of the most iconic breeds of dogs in the world. They were owned by the likes of Queen Victoria, Franklin D Roosevelt, Charles Lindbergh, Humphrey Bogart and many others. These star-studded names and many more owned one or several of these charming little dogs. As their popularity became ubiquitous, the instantly recognizable Scottie incidentally became a powerhouse of advertising. My daughter actually has an antique tin Scottie sign hanging above her desk. Their likeness was used to promote everything from whiskey to kitchen appliances to railway travel.

This fiesty breed was all the rage and on top of the world. But, all good things come to an end, and the reign of the Scottish Terrier’s seat as the most popular dog breed in America was no different. They were overthrown sometime in the late 40s to mid 50s and now enjoy just a fraction of their former glory. But as their numbers in the general population began to slowly dwindle, their prowess in the show ring continued on for significantly longer. And this, unbeknownst to Scottie fanciers at the time, would be their eventual downfall.

There is such a thing in the breeding realm as “popular sire syndrome.” I will spare you my own fumbled attempts at describing this article and instead will defer to a foremost authority on the matter, Dr. Jerold S. Bell of Tufts Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine:

An important issue in breeding is the popular-sire syndrome. This occurs when a stud or tom is used extensively for breeding, spreading his genes quickly throughout the gene pool. There are two problems caused by the popular-sire syndrome. One is that any detrimental genes which the sire carries will significantly increase in frequency – possibly establishing new breed-related genetic disorders. Second, as there are only a certain number of bitches or queens bred each year, overuse of a popular sire excludes the use of other quality males, thus narrowing the diversity of the gene pool.

Every breed has its prominent individuals in the genetic background of the breed. But most of these become influential based on several significant offspring that spread different combinations of the ancestor’s genes over several generations. The desirable and undesirable characteristics of the ancestor were passed on, expressed, evaluated by breeders, and determined if they were worthy of continuing in future generations.

The problem with the popular-sire syndrome is that the individual’s genes are spread widely and quickly – without evaluation of the long-term effects of his genetic contribution. By the time his genetic attributes can be evaluated through offspring and grand-offspring, his genes have already been distributed widely, and his effect on the gene pool may not be easily changed.

In almost all instances, popular sires are show dog and cat champions. They obviously have phenotypic qualities that are desirable, and as everyone sees these winning individuals, they are considered desirable mates for breeding. What breeders and especially stud-dog and tom-cat owners must consider is the effect of their mating selection on the gene pool. At what point does the cumulative genetic contribution of a popular sire outweigh its positive attributes? A popular sire may only produce a small proportion of the total number of litters registered. However, if the litters are all out of top-quality, winning females, then his influence and the loss of influence of other quality males may have a significant narrowing effect on the gene pool.

This is a major concern with all breeding populations of any animal, but the effect is doubled, tripled, and even quadrupled in the instances of rapidly declining populations. As the gene pool shrinks, it becomes more and more challenging to avoid these popular sires.

And in the particular case of Scotties, there were a lot of them.

Bardene’s Bingo took the show dog world by storm in 1967 by becoming only the third Scottish Terrier to win at Westminster. He was widely bred and, more importantly, his pups were widely linebred. This is the practice of breeding related dogs (sometimes even as closely related as mother to son or father to daughter) in order to “set” a particular desirable trait in the line. Most traits that breeders select for, such as desirable ear set or correct body shape, are recessive in nature. Keeping the line “tight” amplifies the genes that produce these traits, but it also has the possibility of eliminating genetic variability.

The Bardene dogs enjoyed such an explosive popularity as studs that even today, their ripples can be seen in even the pet lines. Bardene Scotties had a particular quirk on their tails: a bit of heavily striped brindling around the base or the midsection that became known as “the Bardene ring.” Even though it’s been sixty years, my own dogs have this particular quirk as well.

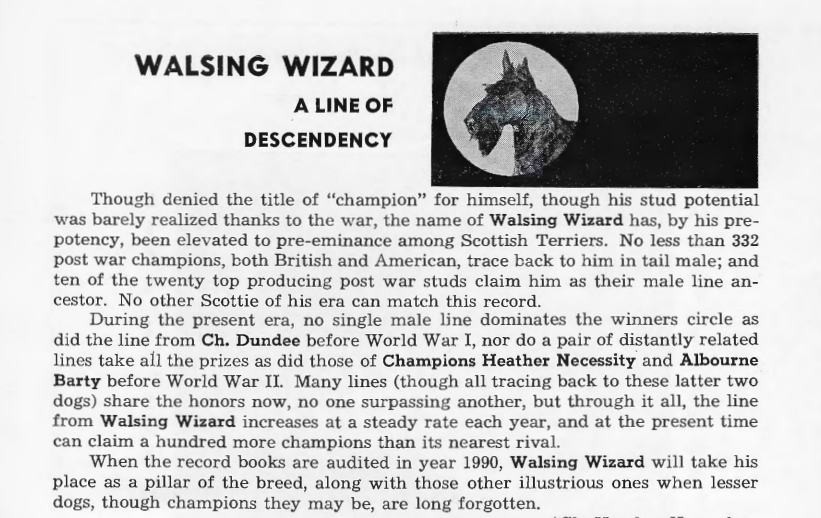

But Bingo was certainly not the only popular sire of his time.

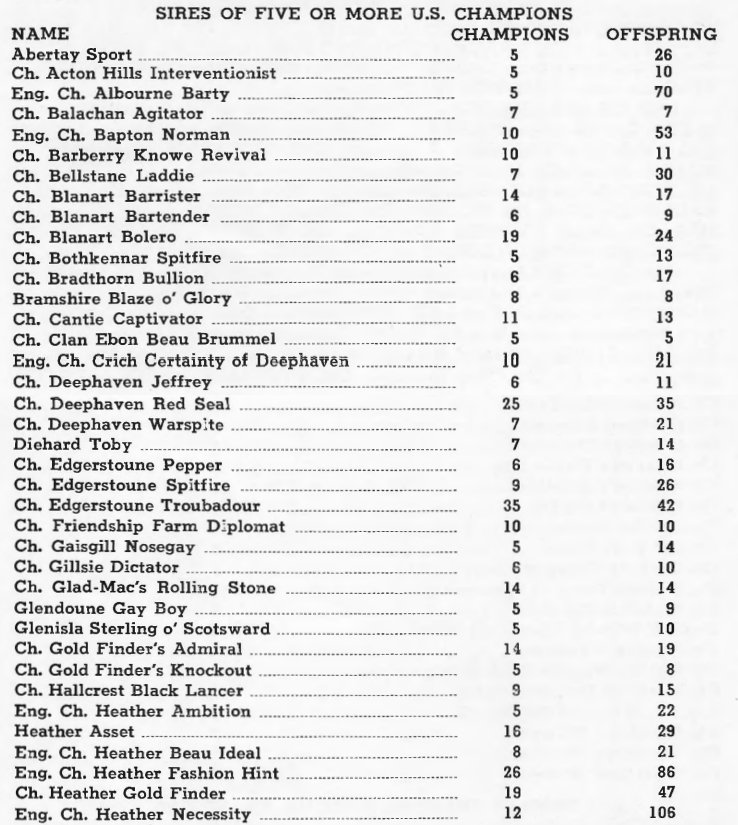

There were hundreds of dogs that produced 30, 40, even over 100 puppies. The most popular sires produced over 300, possibly as high as 500 puppies in their lifetimes. And these pups were subsequently bred back to each other over and over again in order to produce more champions. In fact, it became a point of intense pride to own a “double grandson” of many of these below names.

This continued on for years, even as Scotties became scarcer and scarcer. Their numbers fell precipitously in the 80s and 90s, to the point that breed clubs sounded the alarm about the possibility of detrimental health effects, and possibly even the extinction of the breed altogether. By the mid 2010s, they had been placed on the endangered breed registry in the UK. Registered litters have experienced a small bump in the last ten years or so, but not as much as we stewards would like to see…especially in their ancestral homeland.

The continued disproportion of Scottie dogs used for conformation vs Scottie dogs living as pets has become further amplified as their numbers decrease. In 2018, one out of every three Scottish Terriers puppies born from AKC stock went on to compete in a conformation show. This is wildly out of proportion of other breeds, who often maintain a reservoir of genetic variability within the pet populations and eventing or performance breed lines. Working or event breeders tend to select more for complex behaviors as opposed to physical traits, and complex behaviors are more likely to be governed by dozens of genes instead of just a handful. Therefore, selecting for behavior is inherently more likely to produce “heterozygosity,” or in simple terms, genetic variability.

Scotties, on the other hand, do not have eventing lines of any real significance. The same dogs that are used in conformation shows are the likely ones who compete in other trials such as Fast CAT, Barnhunt and EarthDog…and when they win, it further increases their desirability as breeding animals. The result of all of this has been comparable to a genetic megaphone, loudly broadcasting the same genes over and over again, drowning out everything else.

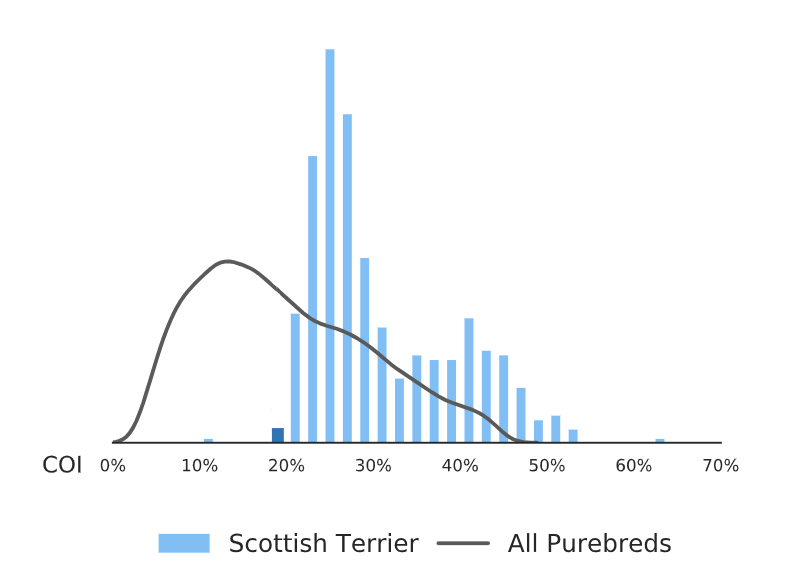

This has resulted in an overwhelming degree of inbreeding within our beloved little dogs. This constant biological copy/pasting in the pursuit of ribbons has led to the current situation we find ourselves in. Scotties have earned the dubious distinction of joining the list of the most inbred studbooks to date. If this seems hard to believe, then you might be interested in this next visual.

Embark, a popular genetic service available to breeders and pet owners, calculates the COI or “coefficient of inbreeding” of their received specimens. The grey line is the average COI of all purebred breeds, and the mean appears to be about 12-14%, give or take. Compare that to the blue bars, which represent Scottish Terriers. The mean here appears to be in the high 30s, at least visually. Goal COI for a healthy breeding population is often quoted as being 6%, but certainly no more than 15%.

Keep in mind that COI is not the end all be all of genetic measurements. There are several other factors in play, namely heterozygosity, RI, OI, and many other factors. It’s actually possible to have two dogs that are very closely related by pedigree and yet have very little genetic material in common. However, this usually occurs in much more populous breeds with a much wider availability of lines, often including those working and eventing lines we talked about previously.

Another visual for you:

Wisdom panel, another popular dog genetics service, measures the degree of heterozygosity in their submitted samples. The higher the degree of heterozygosity, the lower the chance of a puppy inheriting autosomal recessive diseases. This is the heterozygosity result of a Scottie who was bred almost exclusively with genetic variability in mind. Without careful breeding, heterozygosity is lost and diseases such as TCC run rampant.

So…what can be done about all this? Is all hope truly lost for the Scottish Terrier? Certainly not. But we must begin acting now in order to avoid disaster.

Firstly, I believe it is absolutely imperative that a large database of Scottie DNA be built so that factors such as RI and OI can be made accessible to breeders through services such as BetterBred. Fortunately, this effort is already underway! Scottie owners have been submitting their dogs’ DNA for years through a program initiated by the STCA. I applaud this massive effort, but the data itself has not been made readily available to companies or organizations that could put the utilization of it directly into the hands of the breeders in the form of pair predictors. Liberalizing this data would be immensely valuable to the breed. I have high hopes that this will come to pass eventually.

Second, breeders must stop gatekeeping their lines by refusing to issue full registration to puppies they produce. This adds huge roadblocks to prospective breeders who would like to increase the genetic diversity of their dogs. Thirdly, breed standards must be loosened in order to promote the intermixing of dogs who do not perfectly match the textbook. This may sound shocking, but some breeds, such as the Border Collie, do not follow a breed standard for appearance at all (coincidentally, it’s no surprise that the average coefficient of inbreeding of Border Collies ranges somewhere between 5% and 9%). Finally, breeding dogs must be shared across international borders in order to dilute the overrepresented genes within the US and UK populations…and I’m not talking about the popular sires from overseas.

Even if I could wave a magic wand and make all of this a reality overnight, it might still not be enough. The damage may very well have already been done. As TTC is likely to appear after six years of age, it is impossible to breed only dogs who are never diagnosed with it. There also appears to be some degree of environmental factor that triggers the gene to switch on and create tumors. This, unlike autosomal recessive inheritance patterns, is very difficult to track within breeding lines, as it requires breeders to stay in contact with their puppy buyers for an extended period of time.

Our final hope may lie in following the example of Dr. Robert Schiable of The Dalmatian/Pointer Backcross Project. If all else fails, intermixing the other terrier breeds that Scotties sprang from and then backcrossing them with Scotties may be our last resort to ensuring overall good health of the Scottish Terrier. Whether or not our parent breed club would ever choose to acknowledge such dogs as “true Scotsmen” remains to be seen, but I wouldn’t hold my breath. It took the AKC over 30 years to register Dr. Schiable’s Dals, and I believe Scotties would face a sterner fight than he did.

I’m not the only one who holds these views, but at times it sure feels like I am. Whenever I get dejected by yet another nonbeliever, I reread this article to center myself and remind myself of what I’m trying to accomplish.

You may have noticed something else interesting about that Embark graphic. I’ll point it out to you.

See that incredibly far left outlier over there? The one who appears to be around 12%? Did you wonder what breeder was represented by that tiny blip of blue? Did you also wonder whose litter of pups produced the highly heterozygous Scottie, Roland Duchane? Whose dogs are these?

I’ll let you in on the secret.

…They’re mine.